January 2020 Cost to Dispense Study: Tale of Two Stories

The results of a sponsored study on prescription dispensing cost dressed the emperor in new clothes for all to see what he would have you see.

Overview

-

- An industry sponsored Study sets $12.40 as the cost to dispense each prescription, with direct store labor accounting for 58% of this amount.

- Results suggest an average prescription takes 14 minutes to fulfill giving a completion rate of just 4 prescriptions per hour.

- The high cost may be problematic to payors/patients looking for low dispensing cost.

- Visual inspection of pharmacy operations may not support the Study metrics.

- More metrics may be required to support the high drug store cost to dispense.

- Hospital outpatient pharmacy may offer payors and patients higher value product at lower cost.

A recent LinkedIn article argued for higher reimbursements citing dispensing cost from a January 2020 Cost to Dispense Study.[1] PBMs have come under fire for widely believed unfair reimbursement practices. Pharmaceutical companies are balking at 340B contract pharmacy practices they see as unfair. All the while, drug chains and independent pharmacies cry foul by citing the high cost of dispensing.

The Study reported the mean overall cost of dispensing a prescription as $12.40. It reported payroll cost as the biggest drivers accounting for 58%, or $7.22. There is no reason to believe that this number does not accurately reflect data as asked for by the Study.

The first story of the tale ostensibly confirms retail prescription dispensing cost is higher than reimbursement rates, much higher. Labor cost, the most important driver for reimbursement, is a large share of the total cost. If correct, government, PBMs and insurance companies might well be expected to reimburse pharmacies at least $7.22 more than the cost of each medication according to this story. Even then, dispensers stand to lose up to $5.18 on every prescription. As statistics on the emperor’s clothes would have us see.

The Study, however, tells a second story. The reported cost to dispense a product exceeds what buyers are willing to pay. In this context we begin to think in terms of a payor buying a service to deliver a product. Buyers, in a free market, will not buy a product if it cost too much and/or does not provide the required value.[2] The problem is prescription dispensing is no longer a free market.

Payroll Cost

A client processed a clean prescription through the fulfillment process from start to finish without interruption. The prescription was ready for delivery in 2 minutes and 30 seconds. This is not necessarily the best production rate, but it is a good start for our discussion.

First, let us double the client’s test result and use 5 minutes as the amount of time it takes to dispense a prescription. This should pass a litmus test for pharmacies using robotics, computer systems, and vendor sourced prescription-quantity bottles.

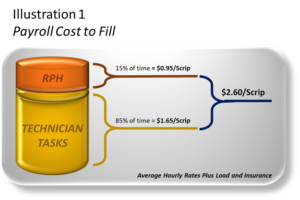

Second, not all fill tasks require a pharmacist license. While it might vary by state, let us say that on average 15% of the actual fill time require a pharmacist license.

Illustration 1 shows the average payroll[3] prescription payroll a vendor might calculate using readily available data and processing time of 5 minutes. It is easy to see how the gap between what the seller demands and what the buyer expects raises concerns.

Illustration 1 suggests it takes $9.80 ($12.40 less $2.60) to deliver $2.60 of product, 3.8x the value of the product. The retail price would still be over twice the product value even if we increase labor cost by 50%.

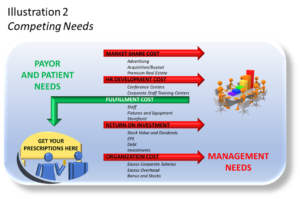

Let us look at the Study’s $7.22 direct labor cost in a broader context. If we reason that direct labor cost is marginal and controllable,

Illustration (3) shows the annual cost of store direct payroll over a range of average daily scrip levels. The Study labor estimate gets into trouble almost from the start suggesting an annual payroll $200,000[4] for 75 scrips and 92 open hours per week. Non-24 hour stores of 500 daily scripts spend $1.4 million on direct payroll according to data the Study presents.

$7.22 translates to 14 minutes for every dispensed prescription. A visible check on the reasonableness of this fill time is that a 250-scrip pharmacy would require one (1) pharmacist and five (5) technicians on duty for every hour the pharmacy is open.

Not passing the blemish test are other assumed patient related cost like consultation and return-to-stock. Having a technician ask a patient if he/she has any questions for the pharmacists should not be the threshold for consultation. And, while return-to-stock adds payroll, payors and other patients should not pay for failure to perform delivery in a reasonable time.

Benefits of the Payroll Product

Another issue that shadows the high Study labor cost is the absence of patient centric services. Despite paying upwards to $9.80 for the $2.60 dispensing service, patients are rarely asked to update their medications for accurate DUR, and in some States, asking a patient if they have a question for the pharmacists rather than proactively addressing potential issues or usage is the norm.

Discretionary Cost

Assuming that payroll cost is less than $7.22/scrip and greater than $2.60/scrip, that leaves a considerable gap to the overall dispensing cost of $12.40. So, what does this second story of the tale suggest?

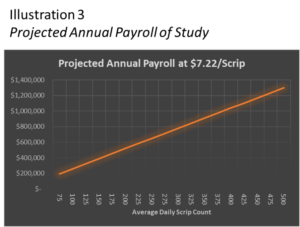

In most every business there are necessary and discretionary cost. There are product delivery costs that serve the buyer (payor). Necessary costs serve customer needs. Discretionary costs serve management and investor goals. Shareholders, not payor/patients, should bear the burden of discretionary costs.

The second story in the tale asks the question if dispensing costs should include discretionary and other non-dispensing management costs, and if so, how much? Payors should be concerned about setting a limit to how much they are willing to pay retail management, executives, and stockholders for their service and capital, especially in a non-competitive market dominated by drug chains.

Illustration 2 contrasts management and payor/patient needs. The former focuses on low cost, accessible, safe fulfillment of prescriptions. We envision independent pharmacies as the symbolic lemonade stand of prescription delivery. These patient centric, low cost, community pharmacies provide the same service as the big drug chains.

Why pay for the overhead of big drug chains? The larger question is why would payors/patients underwrite costs unrelated to the services they need, even failure to perform delivery in the time and manner needed? Why should patients pay more to go out of their way to pick up a prescription that was once conveniently accessible at a local independent or next to a grocer?

Facilities

The most visible discretionary cost is the drug store itself. Commercial hard corners command a premium[5], more so if there is competition for the corner as is the case for drug chains. For those of us old enough to remember, drug chains opted out of traditionally lower cost real estate in favor of these high profile, high traffic, and expensive corners. Did this choice reduce payor/patient cost? Did it improve wait time? Did it improve patient healthcare benefits? Did it add value to the payor/patient? How does building appearance improve patient experience?

The Study allowed contributors to prorate facility cost as a percentage of the pharmacy footprint to the total store. This raises questions as to how drug chains may have calculated the pharmacy footprint. Some drug chains, for example, now include clinics and other non-prescription delivery related areas in pharmacy.

Other Store Cost

This cost category allows contributors to prorate other store costs to the pharmacy based on sales revenue. Payors might take exception to this as one might assume the average prescription transaction revenue is greater than the average front-end basket. This would be particularly concerning for marketing and advertising cost which have nothing to do with the value of prescription dispensing.

Other store costs reflect include burdens of discretionary costs and poor management (if that is the case). Drug chains could include legal fees (defense against payors and patients), charitable contributions (unrelated to delivery of prescriptions), bad debts, interest cost, and ‘other costs not included elsewhere’.

The Study does not explicitly exclude central pharmacy operations and fill so one might assume drug chains are passing the costs burdens of these high overhead, low ROI operations to payors and patients.

Corporate Cost

The Study gives little guidance on corporate cost. This would allow drug chains to include high corporate salaries and bonus, travel, and many other perks, benefits, and discretionary costs in the study.

An Alternative Approach

The Study reported what drug chains want payors and patients to believe is the cost to dispense a prescription. Likely, it is a fair representation of what drug chains spend. But should payors and patients be required to reimburse drug chains for the decisions they make on the behalf of themselves and stakeholders?

Might it be meaningful to sponsor a study to discover the expected real cost to dispense? This would allow payors and patients to decide what they are willing to pay for. It would also identify better, lower cost, prescription dispenser options.

Labor

We already posited a labor model above based on the actual tasks and cost of filling and delivering a prescription. This model offers a framework for bottom-up rather than top-down labor calculation.

Facilities

Modeling the lemonade stand removes discretionary costs. The facility model focuses on what fulfillment and delivery require, not what management chooses for competitive and stakeholder reasons. Recently, a major drug chain began rolling-out small footprint pharmacies as if to affirm the that previous high profile, high cost facilities were unnecessary. The challenge, of course, will be satisfying high corporate overhead with these lemonade stands.

Other costs

Independent pharmacies might serve as a framework for other costs. This allows drug chains to capitalize on economies of scale as should have always been the case. Innovation driven rather than payor subsidized profit.

Better Options to Drug Chains

Unfortunately, drug chains consolidated the industry at the expense of competition. Leveraging their increasing size, drug chains dominate the prescription delivery industry. That is not to say PBMs, governments, and other payors do not contribute to the chaos of the industry.

The industry needs a restart button. It is unlikely that major drug chains will be willing to initiate major transformation, although CVS may be positioned well to do so. Short of this, the options are one or more of the following:

-

- 1. Hospital centric community pharmacies

-

- 2. Multi-hospital alliance of community pharmacies

-

- 3. Alliance of hospital and independent pharmacies

-

- 4. Independent Homestead Protection from drug chains

The hospital centric pharmacy system stand-apart for having the greatest potential as a low cost, benefit-full prescription delivery model. Transformational community pharmacies serve the hospital’s patients and return diversification and patient centric services to the dispensing industry.

An alliance of hospitals might best serve larger markets. The alliance would create economies for pharmacy operations as well as ready access to up-to-date patient health information.

An alliance of hospitals and independent pharmacies creates a symbiotic relation that expands diversification of patient centric benefits unique to communities and capitalizes on existing low-cost dispensing framework. Independent pharmacies would provide certain patients with health tests or other therapeutic outcome services.

Independent pharmacies have long needed trade protection from drug chains able to leverage their size to pirate prescriptions, and ultimately buy-out, independents serving valuable markets. Homestead legislation provides protection by:

1. Requiring buyouts to include the cumulative present value of lost profits from prescription

declines since the buyer entered the trade area.

2. Requiring a lost profit fee for each transferred prescription, or a return of margin after fixed fill fee to the independent pharmacy.

Whatever shape a Homestead Pharmacy Act takes on, the goal is to level the playing field by making it more difficult for drug chains to force independent pharmacies out of business and protect profit streams.

If the Study is to be believed, the cost of dispensing along the current path is increasingly unaffordable, or, points to industry inefficiency that the healthcare system cannot sustain. Both stories of the tale call for change.

Summary

The Study cost categories seem to encompass everything including the kitchen sink. In contrast, payors and patients should only be paying for costs necessary to dispense the prescription.

The first story of the tale conveys a message that the cost to dispense a prescription is extremely high, and if correct, points to a need for a closer look at reimbursement rates over the near term, and an industry transformation over the longer term.

The second story may reveal:

1. Total labor cost is significantly higher (2.8x) than the calculated labor cost based on observable operations.

2. It costs $9.80 to deliver $2.60 of calculated labor, nearly a 4:1 ratio of overhead to delivered product value.

3. Study cost of $12.40 includes allocation methods and costs that may overstate costs attributed to pharmacy.

4. Study allows participants to include costs unrelated to the dispensing of a prescription, such as marketing, costs related to improving market share, excessive management overhead, costs related to improving EPS, dividends, bonuses, and other discretionary costs.

5. The need for an independent study to develop a prescription dispensing cost model for the industry.

6. As was the case of the first, the second story points to a need to push a reset button on the industry.

Footnotes

[1] Prepared by Abt Associates in partnership with the MPI Group, Inc. The report was commissioned by NACDS, NASP, and NCPA..

[2] Amazon is a classic case for a product (brick and mortar stores) that became too costly a delivery system. Consumers replaced the delivery system with Amazon who in turn payed for delivery out of retail prices that include brick and mortar cost.

[3] Average hourly rates sourced from Indeed.com and Glassdoor.com. A 15% load rate covers other payroll cost.

[4] Estimates based on reasonable assumptions splitting dispensing tasks between licensed and non-licensed activity, and published average hourly rates including load and insurance.

[5] Emil Emilov, Investing-in-Property.com.