Readmission Reduction … Fact or Fiction Marketing

There is a difference between stated fact and business sense. In the case of hospital readmission, the facts can be viewed to suggest that readmission penalty policy has improved performance. Business sense would tell us otherwise. Yes, in a perfect world they might work, but not this world. For this reason, appealing to a client’s perceived need to reduce readmission may not be as persuasive as appealing to their need to create revenue and profit.

“Transforming your outpatient pharmacy will help reduce drug/prescription related readmission”, I explained. The client looked back unfazed by this prospect. Was I the only one in the room who saw a reduction in drug related readmission and improved therapeutic output as meaningful healthcare goals? A complicated question and answer for sure. If the metric for his success (and bonus) was profit, how compelling is the prospect for improving outcomes?

I recently read a vendor piece suggesting readmission reduction as a benefit of purchasing a newly unveiled prescription packaging machine. I remember thinking ‘good luck with that’. It was not the machine per se. The machine might offer an opportunity for reducing prescription related readmission under the right transformed process. So too would simply transforming the outpatient pharmacy process. So, what might be the problem with this marketing approach?

The ingenuousness of perceived goals are as suspect in healthcare as retail. This is not to suggest the integrity of doctors, nurses, and rank-and-file pharmacists should be called to question. But business sense tells us compassion is not a good metric and not a sound financial investment. For this reason, appealing to decision-maker compassion or quality of care concern is unlikely to trigger interest unless coupled with revenue and profit.

A Harvard Medical School Study in 2019[1] suggested that the observed reduction in the rate of readmission could just as easily correlate to a reduction in hospital admissions for those six disease states over the same period. Subsequently, CMS data would suggest a more or less uncorrelated and random year-to-year changes overall. Other studies suggest the rise in observation admissions might offer another explanation for the decline in hospital readmission. Still others point at recovery and long-term care center numbers. One might question the ingenuousness of readmission goals on the part of all parties in light of these alternative dialogues.

A hospital which is performing well relative to the served market is unlikely to reduce readmission in any sustainable way short of not serving the higher risk markets. Such a hospital has no choice but to pass along the cost of the penalty, reduce labor to offset the added cost of doing business, or find revenue/profit generating opportunities. Outpatient pharmacy trends since the inception of HRRP would suggest it is one of those profit opportunities. The promise of profit has not been realized for those hospitals operating retail clones.

Readmission rate as a guide to quality care

The HRRP argued that, in addition to the penalty, shining a light on readmission would shame hospitals into reducing readmission rates. While a ludicrous argument from a business sense, no kind of transparency will be effective unless it can be weaponized. And no weapon will be effective when choice is removed from the equation for whatever reason. This concept may have helped harvest votes for approval (a believable ulterior motive), but it is not a practicable consequence from a business sense.

Quality of care concerns are a matter of affordability and leisure. Readmission rates do not matter very much when hospital choice is removed from the equation. A hospital serving the LGBT community in Chicago was the only one where sex reassignment surgery could be performed. A patient critique revealed she was forced to crawl to the bathroom after surgery because the staff was unwilling to care for SRS patients. Making matters worse, a staff member stepped over her as she crawled. The hospital continues to serve the community despite this critique. Many hospitals serve markets where readmission rate is less of a concern than getting admitted in the first place.

The empty bed is king

Even if we accept readmission reduction as a genuine (and doable) goal, hospitals would need to offset the reduction in bed utilization. The brutal truth is that hospitals can be driven by cost absorption necessities that trump other considerations. The average patient generates $3,950 of revenue per day ($15,734 per stay)[2] compared with the average retail prescription price of perhaps $65 (excludes bio and specialty). Additionally, some hospitals are prisoner to self-inflicted wounds such as waste, excess device inventory, poorly designed hospitals, and market potential mismanagement just to name a few.

Dealing with the Consequence of Profitable Pharmacy

A successful outpatient pharmacy program will reduce the risk of drug related trips to the ER and readmission. This presents a challenge for hospitals unprepared to market higher bed vacancy rates. Empty beds mean lost cost absorption opportunity. It is difficult to compare the bed billings to cover $20,000 plus cost with the margin earned on a prescription successfully filled to prevent a readmission. Once again, business sense contrast to the cost of compassion and quality of care.

The over-served market

A client using an outside pharmacy management company to run their outpatient pharmacy struggled with a poor prescription service model that led to endless wait queues where selling a place in line was common practice. Because the pharmacy operated as a drug clone (vendor managed by former chain drug executives), the horrendous wait times were endured only by the uninsured unable to get medications elsewhere. The ER was clogged with individuals returning for refill prescriptions and those who failed to follow discharge prescription instructions.

Because of high readmission rates, in part fueled by a poor prescription delivery model, the hospital could not serve a sufficient mix of insured patients and higher profit disease states in the market. Enter the new hospital across the street. In a touch of irony, the new hospital was purchased and opened by the adjacent institution providing contract doctors who saw the opportunity to serve the insured market at the expense of their client’s poor operations.

This not all-that-uncommon a scenario leads to over-serving available disease states within the market. Too many beds in relation to the market potential. In the scenario above, the client hospital was more than adequate to serve the market disease states. But because they fouled the ER, had high readmission and poor therapeutic outcome they opened the door to a competitor for insured, highly profitable disease states.

I have no doubt I could have turned the pharmacy delivery system around. Had a turnaround occurred, however, they would face the challenge of recapturing their lost share in a now over-bed market. Understandably, the new competitor would react. Too many beds fighting for the same market, a scenario being played out across an industry where effectiveness and efficiency have gone unanswered for too long.

Ready is, ready does

Ignoring the penchant for siloed operations, hospitals must prepare for success of outpatient (in-hospital, in-market) operations. The right outpatient pharmacy business strategy focuses on driving profitable business to the hospital. While readmission reduction for low return disease states and freeing ER capacity are part of the strategy, emphasis must be on creating a profit business model and capitalize on potential hospital synergies.

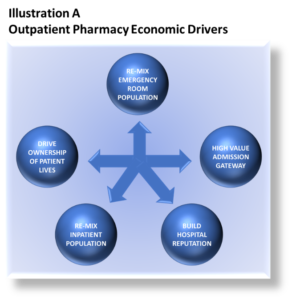

Illustration A suggests just five outcome strategies for the successful outpatient pharmacy business model. It all begins with recognizing the fact that drug chain pharmacy operations are not engineered for a patient-centric healthcare strategy. Drug chains engineer pharmacy operations to place the burden of delivery on the patient both in terms of lost benefits, increased outcome risks, and delivery time. Hospital markets are intolerant to these costs. This offers the disrupter a significant growth opportunity.

The right process transformations and in-market pharmacy tactics (location, site, Etc.), position hospitals to secure a profitable share of the $465 billion industry as reported in 2020.

Right process, right technology

Vendors who demonstrate how their product contributes to revenue and profit rather than reduced readmission might find this a more effective marketing strategy. As a consultant, my focus is always on how a technology can increase profit and pharmacy capacity, while at the same time, reduce time to delivery.

To be successful, outpatient pharmacies must engineer the conversion cycle for the very short window of opportunity. Most, if not all, technology today does little to address the window of opportunity critical for capturing on-campus market share. Vendors engineer technology for retail markets, and outpatient pharmacies are very often secondary or even tertiary markets. In these cases, process must be adapted to the technology rather than the other way around.

In the case of the recently unveiled technology cited above, a focus on revenue and profit might have helped the vendor to tailor technology to better serve the window of opportunity. A response from the vendor suggested that hospital and patient would need to adapt their behavior to the output rate, capacity, and retail use of the machine.

Still, hospitals must be vigilant to vendor revenue and profit claims. A client built-out a significant investment in a central fill facility based on a vendor’s excel revenue/profit worksheet. Upon examination, it was clear the vendor had very little experience in operations engineering. The client’s only recourse were to shut the facility down or operate it as a mail order vendor to the market.

In future articles on technology, I will look at adapting retail technology for hospital markets. One example will be robotic vial filling machines. These machines are not really all that cost effective (when compared with less expensive older machines) for retail. Their use in outpatient pharmacy can be a profit buster and not in the favorable sense. Yet, adapting these machines to a non-retail conversion cycle and process offer new opportunities for market capture, revenue, reduced cost, and profit.

Summary

While hospital readmission remain the literary focus of HRRP, business sense tells us that the cost of reducing readmission can outweigh the penalty. Moreover, there is the presumption that quality of care (or lack thereof) is a primary cause for readmission. This presumption of guilt by the HRRP is essential to its argument that penalties will motivate hospitals to do a better job. The result is that hospital management must be disingenuous about readmission goals and find ways to keep the doors open.

Outpatient pharmacy is one of the ways hospitals hope to create revenue and profit. Unfortunately, major healthcare consultants only have retail drug chains to use as a template and clones do not work. Vendors seeking to build secondary and tertiary markets frame products as readmission reduction tools rather than demonstrate how these retail products can drive revenue and profit for the hospital. In some cases, it would be impossible to do so.

Footnotes

[1] Harvard Medical School, Too Good to Be True?, Jake Miller, November 4, 2019

[2] Debt.org, Hospital and Surgery Cost, Bill Fay, February 26, 2021

[3] Cited by Drug Channels without source citation.

About the Author

Sabrina Hannigan is transsexual who was retired major drug chain as an executive with over three decades experience in site analysis and operations optimization. Upon retiring, she contracted with a healthcare consulting firm to consult on a broad range of operational topics specific to build-out of an outpatient pharmacy service.

As an independent consultant, Sabrina recognized that retail solutions were not transferable and created an outpatient pharmacy business model incorporating methods and processes experienced over forty years in manufacturing and retail.

Sabrina is passionate about the future of healthcare and envisions hospital-centric solutions for improving therapeutic outcome and population health. Towards this end, she continues to develop new processes and methods for outpatient pharmacies.